Imagine a kitchen, not in the distant future of 2050, but in late 2025. It looks familiar: a refrigerator, a stovetop, a smart oven. But on the counter sits a new device, quietly humming as it constructs a complex, beautiful, and nutritionally perfect meal, layer by meticulous layer. This isn’t science fiction. This is 3D food printing, a technology that has moved from a niche gimmick for tech hobbyists to the forefront of a global conversation about the future of food.

For decades, the concept of “printing” a meal was relegated to shows like Star Trek, a futuristic fantasy of instant creation. Today, that fantasy is a tangible reality, and it’s poised to solve some of the most critical challenges of our time. This is not just about creating novel pasta shapes or intricate chocolate sculptures for Michelin-star restaurants—though it does that exceptionally well. This is a technological revolution with the potential to fundamentally redefine our relationship with food.

It promises to tackle crippling food waste, solve complex supply chain issues, deliver hyper-personalized nutrition to hospitals and athletes, and even provide a sustainable way to feed astronauts on a mission to Mars. But what is this technology, how does it actually work, and can it ever overcome the hurdles of speed, cost, and consumer acceptance to earn a permanent place in our homes?

This article delves deep into the 3D food printing revolution. We will explore the sophisticated technology behind the process, the “edible inks” that make it possible, the global problems it’s uniquely positioned to solve, and the very real barriers it must overcome. The future of food is not just being cooked; it’s being printed.

What is 3D Food Printing? The Core Concept

At its simplest, 3D food printing is a form of additive manufacturing. This is a high-tech term for a simple idea: building an object layer by layer from the ground up, rather than the traditional “subtractive” method of carving something from a larger block (like a sculptor).

Think of a standard inkjet printer. It moves a printhead back and forth, depositing tiny droplets of ink on paper to create a 2D image. Now, imagine that ink is an edible puree, and instead of just one layer, the printer adds hundreds or thousands of layers on top of each other to build a three-dimensional object.

The process follows a clear digital workflow:

- The Blueprint (Digital Design): Every print starts as a 3D model, a digital file created using Computer-Aided Design (CAD) software. This file is the “recipe” and the “design” in one, dictating the object’s precise shape, structure, and internal geometry.

- The “Ink” (Food-Grade Cartridges): The printer is loaded with cartridges containing the food “ink.” This isn’t a single, universal substance. It can be any food material that can be pureed, pasted, or powdered, such as:

- Vegetable and fruit purees (carrot, pea, strawberry)

- Doughs and batters (cookie dough, pasta dough)

- Chocolate and confectionery

- Pureed meats (chicken, beef)

- Cheese and dairy products

- Alternative proteins (algae paste, insect protein powder)

- The Print (Layered Deposition): The printer reads the digital file and begins to extrude the food ink through a fine nozzle, tracing the design one layer at a time. Each layer is typically a fraction of a millimeter thick. The process is repeated, with each new layer bonding to the one below it, until the entire, complex 3D food item is complete.

This method allows for a level of precision and geometric complexity that is utterly impossible for human hands or traditional food manufacturing to replicate.

The Technology: A Deeper Look Under the Hood

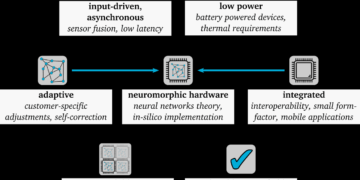

While “extrusion” is the most common method, it’s not the only one. The field of 3D food printing employs several different technologies, each suited for different materials and applications. Understanding these is key to seeing the technology’s true potential.

A. Extrusion-Based Printing (The Workhorse): This is the technology described above and the one most people associate with 3D food printing. A syringe-like extruder, driven by a motor or compressed air, pushes the food paste out of a nozzle.

- Best For: Viscous, paste-like materials (purees, doughs, chocolate, frostings).

- Challenge: Maintaining a consistent flow and temperature. Chocolate, for example, must be kept within a very narrow temperature range to remain printable but still solidify properly.

B. Binder Jetting (Building with Powder): This method uses a bed of fine food powder (like sugar, flour, or spice blends) as its base. A printhead moves across the bed, selectively spraying tiny droplets of an edible liquid “binder” (like water or a sugar solution).

- Best For: Powdery materials, especially sugar. It’s used to create incredibly intricate, full-color sugar sculptures, custom candies, and dissolvable flavour pods.

- How it Works: The binder causes the powder to stick together, forming one layer. The powder bed then lowers, a new layer of powder is spread on top, and the process repeats. The un-bound powder is simply brushed away at the end.

C. Selective Laser Sintering (SLS): This is a more advanced and less common method for food. Similar to binder jetting, it uses a bed of powder. However, instead of a liquid binder, a high-powered laser is used to heat and “sinter” (fuse) the powder particles together.

- Best For: Powders with a high sugar or fat content that can be melted and re-solidified by a laser.

- Challenge: It is expensive, and controlling the “cooking” aspect from a food-safety perspective is complex.

D. Bioprinting (The Cultured Meat Frontier): This is perhaps the most revolutionary and high-stakes application. Bioprinting is an advanced form of 3D printing that uses “bio-inks”—in this case, living animal cells (stem cells) suspended in a nutrient-rich hydrogel.

- The Goal: To print a structured, complex piece of cultured meat, such as a steak or a fish fillet.

- How it Works: The bioprinter deposits different cell types (muscle cells, fat cells, and vascular cells) in a precise 3D architecture to mimic the marbling and texture of a real cut of meat. The printed structure is then placed in a bioreactor to grow and mature. This technology is the key to moving beyond “cultured ground beef” and into the realm of high-value, structured meat products.

Solving the World’s Biggest Problems

The real-world applications for 3D food printing are far more profound than just culinary novelty. This technology is being developed as a serious solution to some of the planet’s most pressing issues.

A. Hyper-Personalized Nutrition and Healthcare: This is the single most valuable application, attracting massive investment. The “one-size-fits-all” model of nutrition is inefficient. A 3D food printer can create meals tailored to an individual’s exact, data-driven needs.

- Hospitals and Nursing Homes: This is a game-changer. Patients with dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) are often given unappetizing, shapeless purees. A 3D printer can take that same nutritious puree and recreate the shape of the original food (e.g., a chicken drumstick or a broccoli floret). This visual cue dramatically increases patient dignity and appetite, reducing malnutrition.

- Precision Dosing: A printer can create a meal with the exact amount of 1,200 calories, 30g of protein, 500mg of sodium, and fortified with specific doses of Vitamin D and B12. This is invaluable for elite athletes, diabetics, and individuals with specific food allergies.

B. Tackling the Food Waste and Sustainability Crisis: The global food system is notoriously wasteful. A significant portion of fruits and vegetables are discarded simply because they are “ugly” or misshapen, even though they are perfectly nutritious.

- Upcycling “Ugly” Food: 3D printing doesn’t care what the food looked like. These “ugly” items can be converted into high-quality purees, which serve as the perfect “ink,” instantly rescuing them from the landfill.

- Alternative Proteins: The technology is an ideal vehicle for introducing more sustainable proteins. Purees made from algae, pulses, or even insect protein (which is highly nutritious) can be used as a base, making these new food sources more palatable and visually appealing.

C. Revolutionizing the Food Supply Chain: Our current food supply chain is long, complex, and fragile. 3D printing enables on-demand, localized food production.

- Reducing Logistics: Instead of shipping bulky, perishable finished food products across continents, a company could ship shelf-stable food cartridges. The final meal is then “manufactured” at the point of consumption—in a restaurant, a supermarket, or even a military base.

- Food in Extreme Environments: This is why NASA has been a key investor in this technology for years. How do you feed astronauts on a 3-year mission to Mars? You can’t pack enough food. A 3D printer with cartridges of long-lasting, powdered nutrients is the most viable solution.

The Challenges: Why Isn’t This in Every Kitchen?

Despite its incredible potential, you cannot walk into a store and buy a kitchen-ready “food replicator” today. The technology is still facing significant hurdles that must be overcome before it achieves mass-market adoption.

A. The Speed Problem: This is the most significant barrier. Most 3D printers are slow. Printing a single, complex cookie might take 10 minutes. Printing a full, multi-component meal could take hours. This is simply not practical for a busy family that needs dinner on the table in 30 minutes. The development of multi-nozzle printers that can extrude different materials simultaneously is helping, but it’s a major engineering challenge.

B. The Texture and Taste Hurdle: A 3D printer can perfectly replicate the shape of a steak, but it cannot yet replicate the texture. The “mouthfeel,” the flakiness of a croissant, the crispness of a potato chip, or the fibrous “bite” of a chicken breast—these are the holy grails of food science. They are the result of complex, microscopic structures that extrusion-based printing struggles to recreate.

C. The “Hot Food” Problem (The Cooking Process): Most food inks are printed at room temperature or slightly warmed. This means the food comes out uncooked. This is fine for chocolate or a salad, but not for a burger or a loaf of bread. The next generation of printers is integrating cooking elements—such as lasers for “printing” grill marks or infrared heat—but combining the precision of printing with the high heat of cooking is incredibly difficult.

D. Cost and Consumer Acceptance: Commercial 3D food printers can cost anywhere from $5,000 to over $100,000. While cheaper consumer models are emerging, they are still far from an affordable kitchen appliance. Beyond the cost, there is the “yuck factor.” Many consumers are instinctively wary of “lab-grown food” or “printed paste.” Overcoming this psychological barrier will require time, education, and, most importantly, producing food that is undeniably delicious.

Conclusion

Do not expect a 3D food printer to replace your oven or your favourite knife anytime soon. The future of this technology is not one of replacement, but of integration.

Picture a kitchen in 2030. Your smartwatch and biometric sensors have tracked your activity, sleep, and nutrient levels for the day. You’re low on iron and Vitamin C. You communicate this to your smart kitchen. Your 3D printer, now an integrated part of your counter, begins to print a small, intricate side dish made from a spinach-and-algae puree, fortified with an exact dose of iron. Simultaneously, it prints a complex, fruit-based dessert, perfectly portioned. While this happens, you are still traditionally cooking the main course.

The 3D printer will not be the chef; it will be the nutritionist’s assistant. It will handle the tasks that require absolute precision, personalization, and sustainability. It will be the tool that finally allows us to treat food not just as fuel or pleasure, but as personalized, data-driven medicine. The revolution has begun, and it promises to be delicious.