Memory is the tapestry of the self. It is the intricate, beautiful, and terrifyingly fragile thread that connects our past to our present, informing every decision, every emotion, and every facet of our identity. For decades, the loss of this tapestry—whether stolen by the slow, cruel march of Alzheimer’s disease, erased by the sudden trauma of a brain injury, or simply faded by the fog of age—has been one of medicine’s most profound and seemingly unbeatable challenges. To lose one’s memory is, in many ways, to lose one’s self.

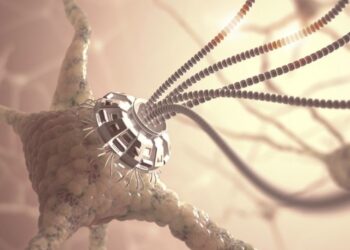

But as of late 2025, we are standing on the precipice of a revolution that could rewrite this fundamental human tragedy. What was once the exclusive domain of science fiction is now the concrete frontier of modern neuroscience. We are talking about neural interfaces, or Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs), sophisticated implants designed not just to read the brain’s signals, but to write to them. These devices are the first tangible hope for a “prosthetic” for the mind—a way to bridge the gaps in a failing neural circuit and, for the first time in history, restore memories that were thought to be lost forever.

This is not a distant dream. The science is active, the early clinical trials are underway, and the initial results are staggering. This article will explore the groundbreaking science behind these “memory pacemakers,” from the complex biology of how we forget to the specific technologies that are learning to help us remember. We will also confront the immense technical and ethical mountains we must climb on the path to a future where “I forgot” is no longer a permanent state, but a treatable condition.

The Anatomy of Forgetting: Why Memory Fails

To understand how we can possibly “restore” a memory, we must first understand what a memory is and how it breaks. A memory is not a tiny, discrete file stored in a single neuron. It is a complex, decentralized pattern of electrical and chemical connections firing in a specific sequence across millions of neurons. The act of “remembering” is the act of reactivating that specific pathway.

Memory loss, therefore, is not the deletion of the file; it is the destruction of the pathway. It’s as if a librarian (your hippocampus) still has the reference card for a book, but the bridges and roads (your neural pathways) leading to the shelf where the book is stored (your neocortex) have collapsed.

A. The Biological Culprits: Several conditions are known to cause this catastrophic collapse, making them the primary targets for neural interface therapy.

- Alzheimer’s Disease (AD): This is the most well-known culprit. In an Alzheimer’s brain, two rogue proteins—amyloid plaques and tau tangles—accumulate. The plaques build up between neurons, disrupting communication, while the tangles build up inside them, destroying the cell’s internal transport system. This combination effectively severs the neural pathways, isolating memories until they are unreachable.

- Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI): A sudden, physical impact to the head can cause widespread and immediate damage. It can tear axons (the “wires” connecting neurons) and cause inflammation that leads to cell death. This results in “gaps” in the neural map, particularly affecting episodic memory—the ability to recall specific life events.

- Dementia and Stroke: Other forms of dementia, as well as major strokes, create “dead zones” in the brain by cutting off blood supply, leading to the death of entire clusters of neurons and the memories they once encoded.

B. The Hippocampal Bottleneck: The key player in all of this is a small, seahorse-shaped structure deep in the brain called the hippocampus. The hippocampus acts as the brain’s “memory formation engine” or “chief librarian.” It takes new, short-term experiences and begins the process of “encoding” them into a stable, long-term memory, which is then “stored” in the neocortex.

Crucially, in conditions like Alzheimer’s, the hippocampus is one of the very first regions to be attacked. When the hippocampus is damaged, the brain loses its ability to properly form new memories and its ability to retrieve old ones. The roads are cut off at the main junction. This is precisely where the first neural interfaces are focusing their revolutionary efforts.

The “Pacemaker for the Brain”: How Interfaces Work

The concept of a memory-restoring neural interface is often called a “hippocampal prosthesis.” The goal is not to store memories on a silicon chip, but to bypass the damaged biological tissue and help the brain do its own job again. It’s a “pacemaker for the mind,” providing a corrective electrical jolt to complete a broken circuit.

This technology is the result of decades of research, most notably pioneered by the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) under its “Restoring Active Memory” (RAM) program. As of 2025, this research has moved from animal models to the first human clinical trials.

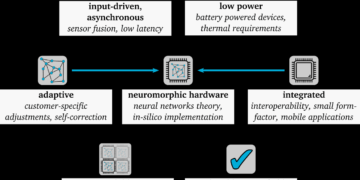

The process is breathtakingly complex, but it can be broken down into three main phases: Reading, Decoding, and Writing.

A. Phase One: Reading the Neural Code First, a tiny, biocompatible array of micro-electrodes is surgically implanted into or near the hippocampus. This device “listens” to the brain’s electrical activity. When a person is successfully forming a new memory (for example, looking at a picture and remembering it 30 seconds later), the device records the precise, unique pattern of neural firing associated with that successful “encoding.”

B. Phase Two: Decoding the “Code for Memory” This is where machine learning comes in. The device’s processor analyzes thousands of these successful “encoding” events. It begins to build a personalized mathematical model for that specific patient, identifying the specific electrical signature that means “a memory is being successfully stored.” It finds the patient’s unique “neural code for memory.” This is not the code for the memory itself, but the code for the act of remembering.

C. Phase Three: Writing the Code Back This is the restorative step. Later, when the brain tries to form a new memory and fails (due to damage from TBI or Alzheimer’s), the device detects this weak or “broken” signal. Instantly, it computes the correct encoding pattern based on its model and sends a tiny, targeted pulse of electricity back into the relevant neurons. This “neurostimulation” doesn’t implant a memory; it facilitates the brain’s own natural process. It acts as a cognitive bridge, helping the weak signal cross the damaged gap and successfully form the connection, solidifying the new memory.

From Science Fiction to Clinical Reality (As of 2025)

This isn’t just theory. The progress in the last few years has been astonishing, moving from simple animal tests to life-changing human applications.

A. Early Successes (The Foundation): Initial studies by researchers like Dr. Theodore Berger and his team, funded by DARPA, demonstrated this principle in rodents and non-human primates. They showed that by recording and stimulating the correct neural patterns, they could reliably improve the animals’ performance in memory-based tasks, even after the animals’ memory was temporarily impaired.

B. The First Human Trials: TBI and Epilepsy: The first human trials focused on patients who already had brain implants for other reasons, such as monitoring epileptic seizures. In these trials, scientists proved that this “closed-loop” system (read, decode, write) could work in a human brain. In studies published over the last two to three years, researchers have repeatedly shown they can boost short-term memory performance in human subjects by 30% to 50%.

C. The Alzheimer’s Frontier (The Present): As of 2025, the most exciting developments are the first-stage clinical trials targeting patients with early-onset Alzheimer’s and TBI. While these results are still preliminary, the reports are profoundly hopeful.

- Hypothetical Case Study (Based on current trial goals): “Patient A,” a 58-year-old with early-onset Alzheimer’s, was enrolled in a trial. Before the implant, their ability to recall a list of words after 10 minutes was near zero. After the device was implanted and calibrated over several weeks, the patient began to show marked improvement. The device, by stimulating their hippocampus at the precise moment of encoding, was helping them “hold on” to new information. This wasn’t a cure, but it was a tangible restoration of function—a lifeline back to the present.

These trials are the critical first step in proving that this technology is not only feasible but safe for long-term use in the patients who need it most.

The Mountain We Still Must Climb: Immense Hurdles

Despite the optimism, we are at the very beginning of this journey. The challenges separating these early trials from a widely available treatment are monumental.

A. The Engineering Challenge: Power and Biocompatibility A neural interface is an incredibly complex piece of hardware that must live inside the human body’s most sensitive environment.

- Power: How do you power it? Early models used wires, but for long-term use, the device must be wireless. This requires sophisticated wireless charging technology that can pass power safely through the skull without heating the brain tissue.

- Biocompatibility: The brain’s immune system is designed to attack anything foreign. Over time, it can form scar tissue (gliosis) around the electrode array, “insulating” it and degrading its ability to read signals. Creating materials that the brain accepts for decades is a massive materials science hurdle.

- Data Processing: The implant must perform complex machine learning calculations in real-time. This requires a powerful, low-energy processor that can fit on the head of a pin.

B. The “Neural Code” Problem: Complexity The current breakthroughs are focused on short-term, “episodic” memory (e.g., “Where did I put my keys?”). This is already incredibly difficult. But what about restoring complex, autobiographical memories (“How did I feel at my wedding?”) or semantic memories (“What is the capital of France?”)? These are stored differently, across vast, distributed networks. Cracking the code for these types of memories is an order of magnitude more complex.

C. The Surgical Risk: Invasive by Nature This is not a wearable. It is not a pill. It is invasive brain surgery. This carries inherent risks of infection, bleeding, and damage to healthy tissue. For the technology to be viable, the potential benefit must always massively outweigh this significant surgical risk.

Editing Our Past: The Ethical Minefield

As with any technology that touches the human brain, the ethical questions are as profound as the scientific ones. These are not just challenges to overcome, but questions we must answer as a society.

A. The Authenticity of Memory: If a device helps you form a memory, is it truly your memory? What if the device, in trying to “bridge a gap,” makes a mistake? Could a malfunctioning implant create a false memory? The line between assisting a natural process and artificially creating a new one is terrifyingly thin. Our sense of self is built on the narrative of our past. Tampering with that narrative is tampering with our identity.

B. The New “Cognitive Divide”: This technology will be astronomically expensive for decades. We are on the verge of creating a new, terrifying form of inequality: a “cognitive divide.” Will the wealthy be able to buy perfect memories, enhancing their cognitive function and securing advantages in education and business, while the rest of society is left to decline naturally? This goes beyond medicine and into the realm of human enhancement.

C. Security and “Brain-Hacking”: If a device can read and write to the brain, it can be hacked. The very concept of “brain-hacking” is the ultimate violation of privacy. Imagine a malicious actor deleting a user’s memories, implanting false ones, or holding a person’s entire identity for ransom. Securing these devices is not just an IT problem; it is a human rights imperative.

D. The Nature of Forgetting: Finally, is it even desirable to have a perfect memory? Forgetting is a crucial biological function. It allows us to heal from trauma, to move past grief, and to make space for new learning. A life without forgetting could be a life trapped in the prison of its own past, unable to forgive or evolve.

The Future of What We Are

The path forward is fraught with challenges, but the destination is too important to ignore. The work being done in neural interfaces in 2025 is not about creating superhuman cyborgs or achieving digital immortality. It is about fighting back against the diseases that unravel the human mind. It is for the TBI victim who can’t remember their children’s names, and for the Alzheimer’s patient who feels their partner of 50 years slipping away into a fog.

The first generation to benefit from this will not have their entire past restored at the flip of a switch. But they may be the first generation that can halt the progression of memory loss in its tracks. They may be able to hold on to new memories—the grandchild’s birthday, the conversation from this morning—and in doing so, remain present, connected, and whole.

Neural interfaces will not just change how we treat a disease; they will change how we define what it means to be human. The ethical debates are essential, but they must not be a barrier to progress. They must be the guardrails that guide us responsibly toward a future where the self is no longer a fortress easily breached by time and disease, but a home we can secure.